Introduction to Conventional Invasive Ventilation

Introduction to Conventional Invasive Ventilation

Dec 02, 2025

Introduction to Conventional Invasive Ventilation

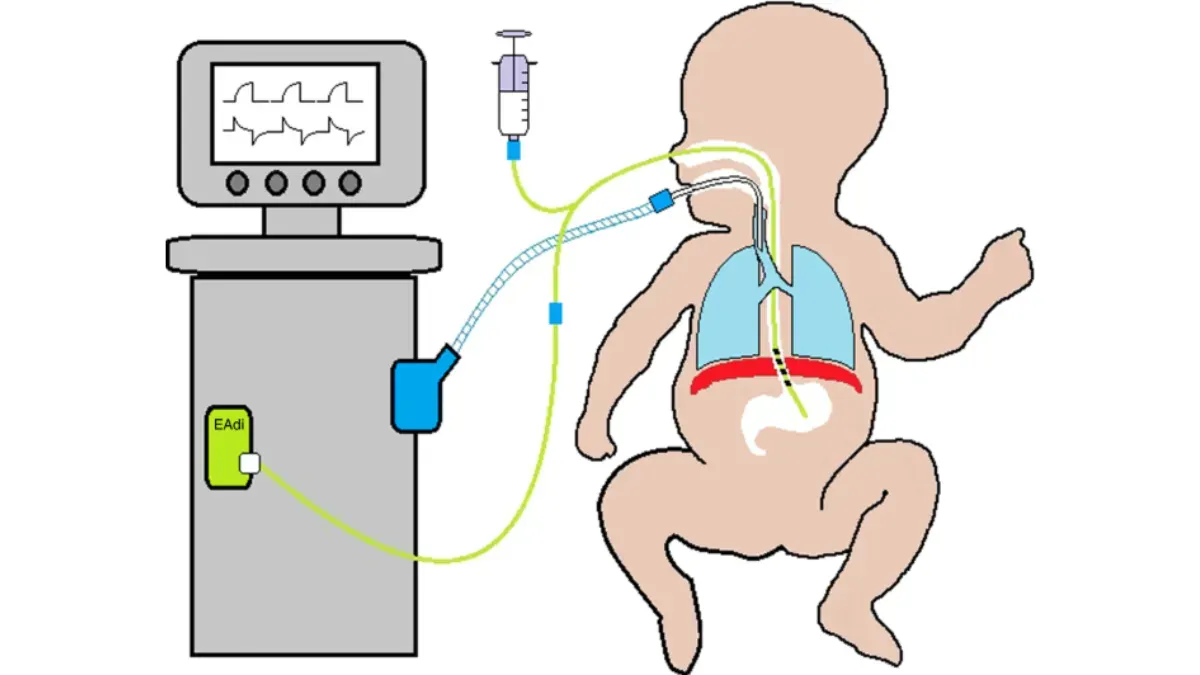

Invasive conventional ventilation has saved countless lives, yet it carries important pitfalls and complications. Because it is not a physiological form of breathing support, clinicians must understand it thoroughly to ensure patient safety. This chapter introduces the fundamentals of conventional invasive ventilation in paediatric practice. It reviews the essential physiology that underpins mechanical ventilation. The chapter also outlines key indications and clinical goals to guide safe and effective ventilatory management.

Introduction

- Normal spontaneous breathing generates negative intrapleural pressure, this creates a gradient that results in airflow from the atmosphere into the alveoli.

- Invasive ventilation is not physiological.

- Mechanical ventilation involves administration of positive airway pressure.

- Understanding the normal physiology of ventilation and the basics of ventilation will ensure appropriate patient management and minimize lung damage.

Basic physiology and physics related to ventilation

- In positive pressure ventilation: pressure is needed to cause a change in flow of gas to enter the airway and to allow volumes of gas to fill the lungs.

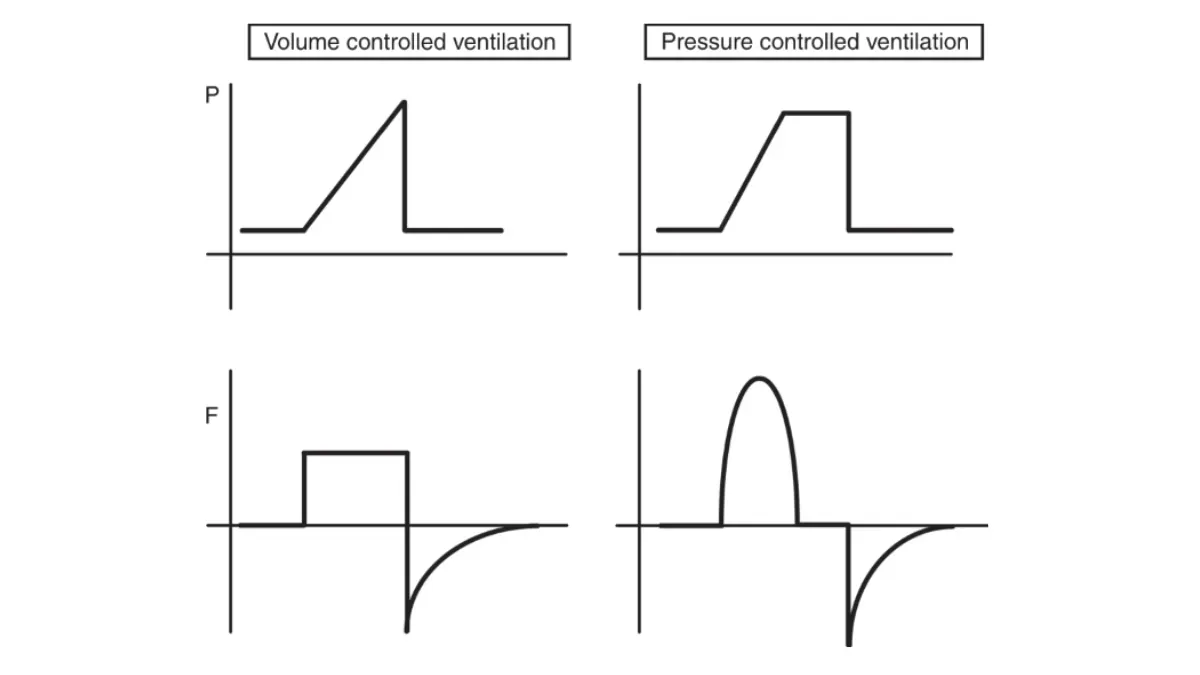

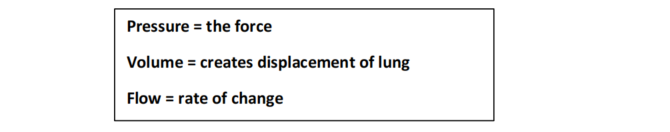

- The physics underlying mechanical ventilation can be effectively described with the use of three key parameters: pressure, volume, and flow.

- This is pivotal in understanding how ventilators manipulate lung mechanics to facilitate positive pressure ventilation.

- Pressure refers to the force applied to create airflow within the ventilatory circuit and into the patient’s lungs.

- The product of flow over time results in tidal volume (VT), which is the amount of air delivered with each breath.

Compliance and resistance

- Paediatric invasive ventilation requires a detailed understanding of the dynamic interplays between airway resistance and lung compliance.

- Each parameter set on the ventilator directly influences the physical properties of the lung and airways.

Pulmonary compliance

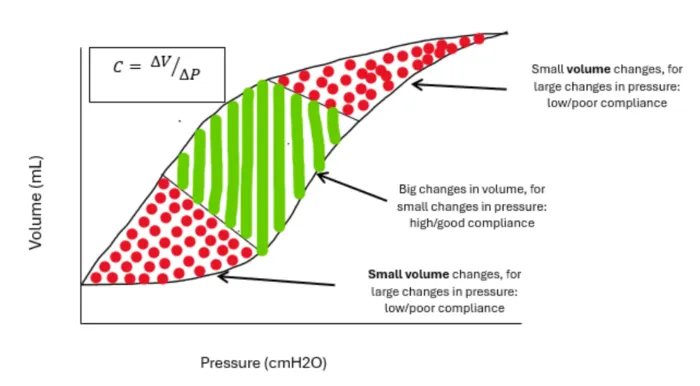

- Pulmonary compliance refers to the ease with which the lungs and chest wall expand during inhalation.

- In mathematical terms, compliance (C) is defined as the change in volume (ΔV) over the change in pressure (ΔP). See figure 1.

Figure 1: Compliance curve explained

Airway resistance

- Airway resistance to airflow in the paediatric respiratory system is complex but mostly influenced by airway/tube diameter, length, and flow character through the airways.

- Resistance (R) refers to the level of pressure needed to maintain a specific flow of gas, and it is calculated as the ratio of pressure change to flow.

- Relationship between resistance and flow is also related to 4th power of the radius.

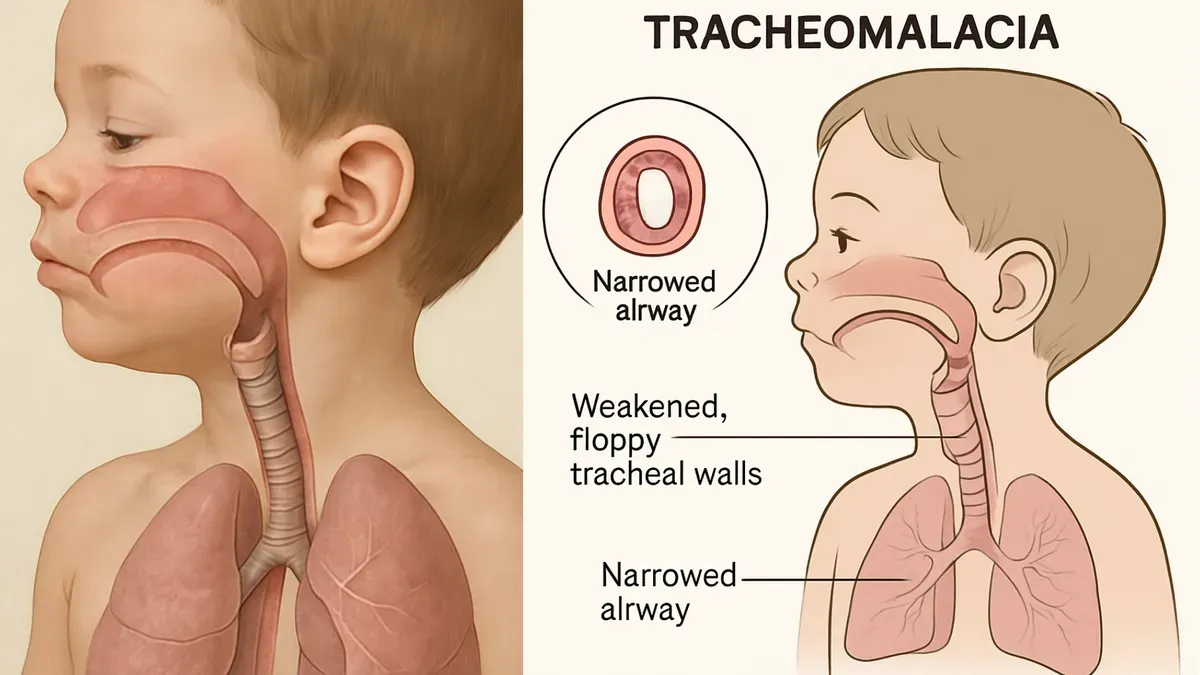

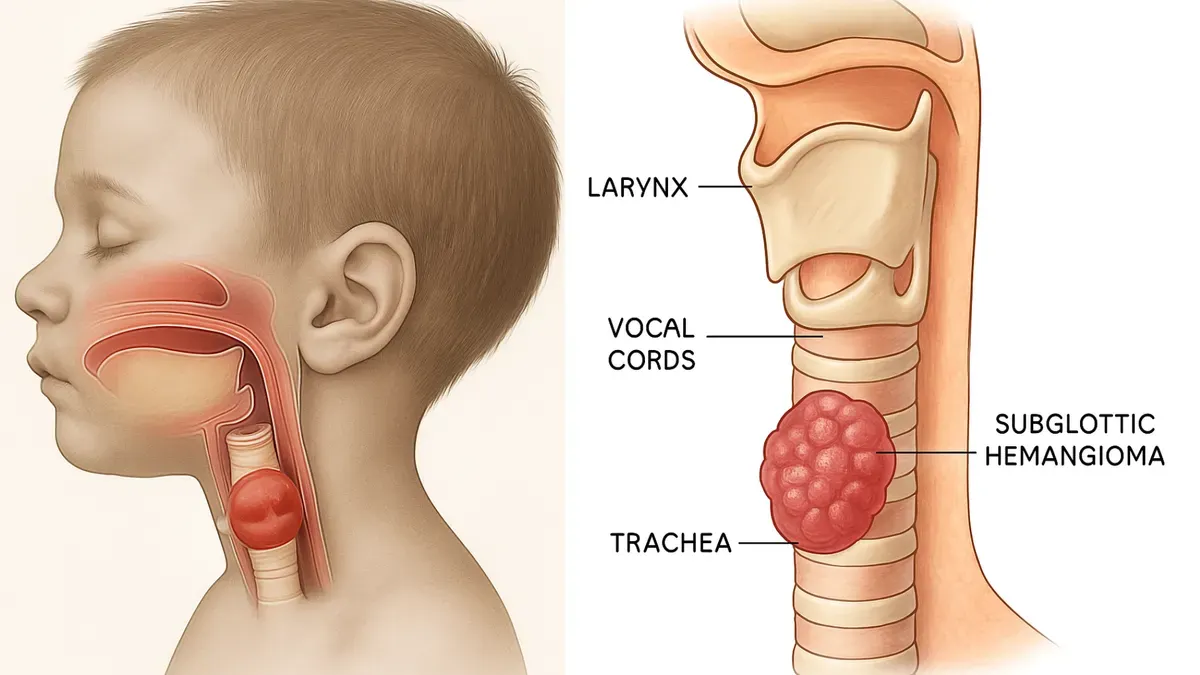

- Children and especially infants have narrower airways than adults, which naturally leads to higher resistance.

- High resistance can particularly be challenging in pathological states such as bronchiolitis or asthma where inflammation, mucus production, and bronchospasm further narrow the airways.

- These conditions demand careful consideration of the peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) and the flow rates delivered during mechanical ventilation.

- The inspiratory flow rate, respiratory rate and I:E (inspiration to expiration) ratio should be adjusted according to the airway resistance to optimize the time for gas exchange and minimize the risk of air trapping.

Indications for invasive ventilation

- Respiratory failure:

- Poor oxygenation with high FiO₂ requirements

- Ventilation problems: hypercarbia or concerns with gas exchange

- Severe respiratory distress with increased work of breathing

- Respiratory pump failure (neuromuscular conditions, weakness)

- Airway protection (e.g. severe neurological depression GCS < 8 or on AVPU responding to pain or below)

- Cardiovascular instability

- Severe upper airway obstruction

Goals of ventilation

- Acceptable oxygenation - monitoring of SpO₂/FiO₂ ratio (non-invasive ventilation). Target saturations 92–97% and FiO₂ < 0.6 and oxygenation index (OI) in invasive ventilation.

- Acceptable ventilation (carbon dioxide), this sometimes may include permissive hypercapnia as part of lung protective ventilation.

- Optimize cardiovascular function.

- Patient comfort:

- Adequate analgesia to minimize pain and discomfort

- Adequate sedation (if required)

- Optimize patient–ventilator synchrony

- Minimize lung damage:

- Employing lung protective strategies

- Promote and facilitate weaning from ventilator as soon as possible