Tracheomalacia

Tracheomalacia

Dec 03, 2025

Tracheomalacia

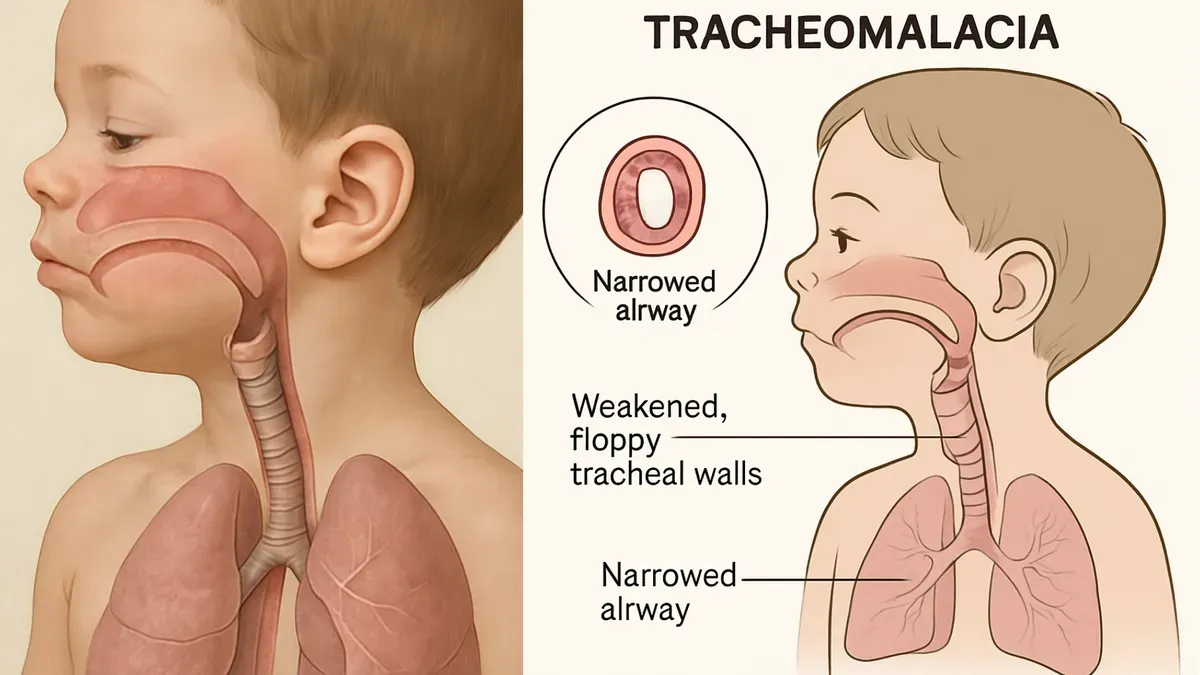

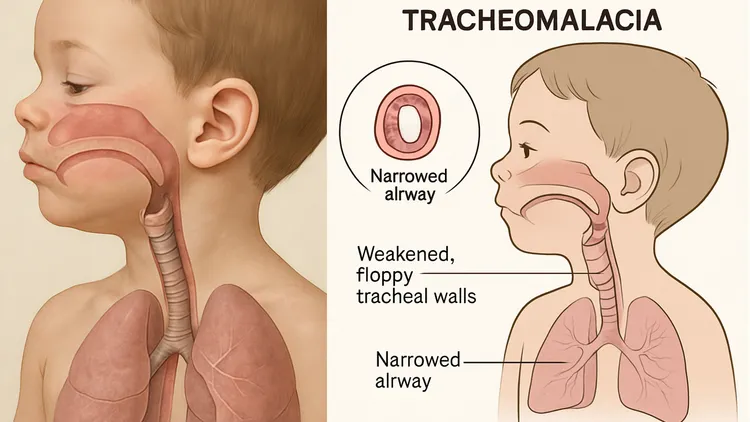

Tracheomalacia is a common condition encountered in paediatric respiratory practice and can significantly affect airway stability. Early diagnosis is crucial to ensure timely and appropriate management. This chapter outlines the key clinical features that help clinicians recognize tracheomalacia in children. It also reviews the diagnostic tools used to confirm the condition, including dynamic imaging and bronchoscopy.

Introduction

- Tracheomalacia is characterized by excessive tracheal collapsibility due to compromised cartilage integrity or posterior wall laxity, leading to dynamic expiratory airway collapse during breathing, especially on forced expiration.

- Congenital tracheomalacia occurs in approximately 1 in 2,600 live births. The true incidence, including acquired forms, may be higher due to underdiagnosis.

- Pathologically, an increased muscle-to-cartilage ratio is observed, with trachealis widening relative to cartilage rings, altering the normal 1:4–1:5 ratio to approximately 1:2.

Terminology

- Tracheomalacia: >50% expiratory reduction in luminal area during quiet respiration.

- Tracheobronchomalacia: if main bronchi involved.

- Bronchomalacia: one/both mainstem bronchi or segmental bronchi affected.

- Severity of tracheomalacia:

- Symptom severity does not always correlate with anatomical severity.

-

- Mild (50–75% collapse)

- Moderate (75–90% collapse)

- Severe (>90% collapse)

Causes and Risk Factors

| Primary (Congenital) | Secondary (Acquired) |

|---|---|

|

|

Clinical Features

- Symptoms depend on site, severity, whether involvement is localised or general, and whether tracheomalacia is primary or secondary.

- According to site:

- Intrathoracic:

- Monophonic non-variable wheeze.

- Barking or brassy cough.

- Recurrent or prolonged respiratory infections.

- Dyspnoea and “dying spells”.

- Extrathoracic:

- Stridor.

- Intrathoracic:

- According to severity:

- In severe cases, symptoms appear at birth, but most babies start showing signs when they are 2–3 months old.

- Feeding difficulties may be present.

- Symptom aggravation:

- Worsened by increased respiratory effort (coughing, crying, feeding, valsalva manoeuvres, exercise, forced expiration).

- Supine position may worsen symptoms while prone positioning relieves symptoms.

- In secondary tracheomalacia, clinical manifestations of the underlying condition will also be present.

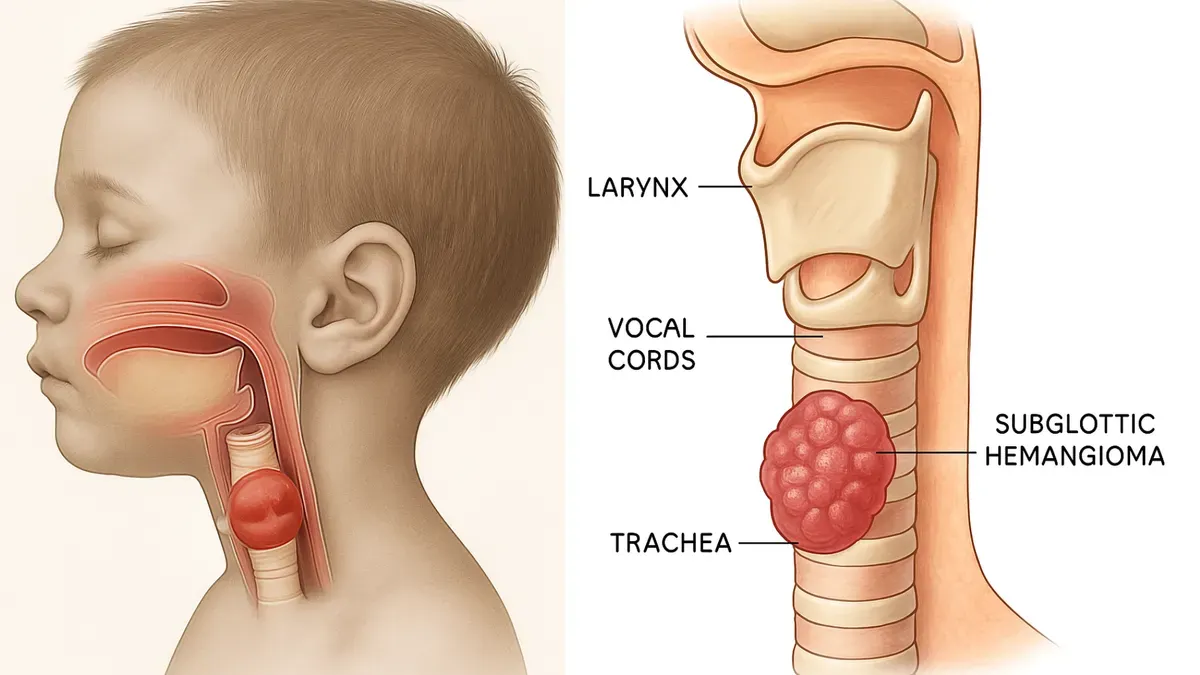

Differential Diagnoses

- Laryngomalacia

- Vocal cord paralysis

- Subglottic stenosis

- Tracheal stenosis

- Vascular rings

- Foreign body aspiration

- Recurrent croup

Investigations

- Imaging

- Chest X-ray (AP and lateral) to assess airway anatomy.

- Contrasted CT chest or MRI is rarely required if the clinical picture is strongly suggestive of tracheomalacia. However, if other mediastinal pathologies (e.g. vascular anomalies) are suspected, it is prudent to perform these prior to flexible bronchoscopy.

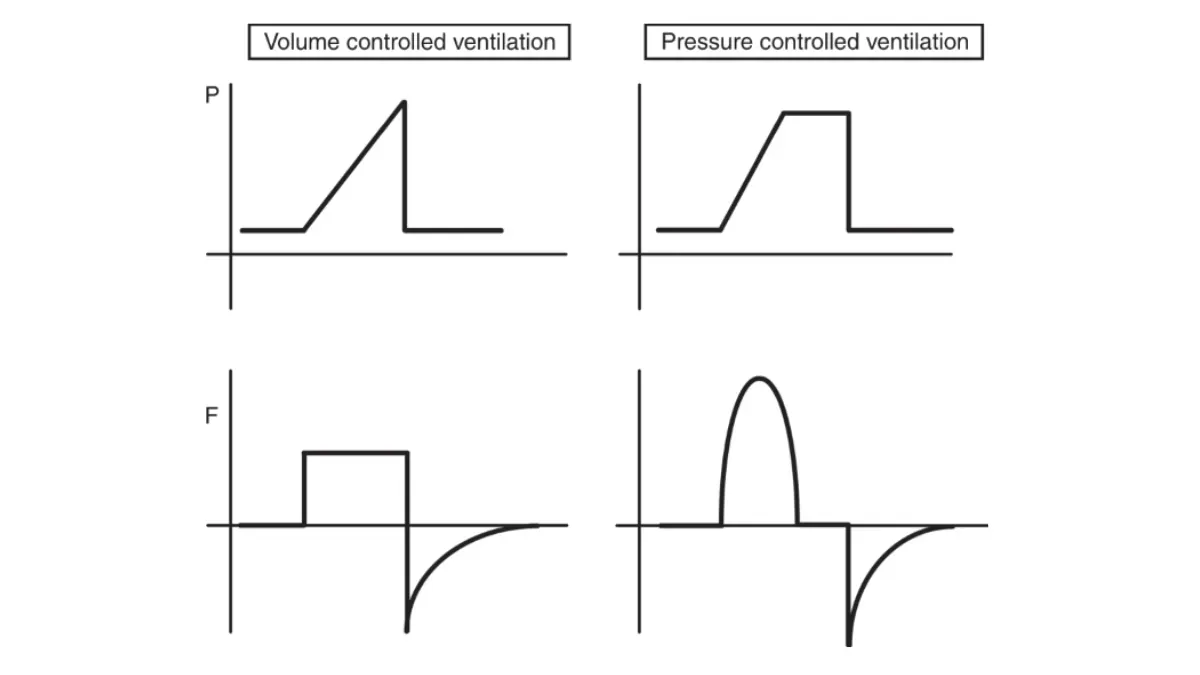

- Spirometry

- In older children, can demonstrate large airway obstruction.

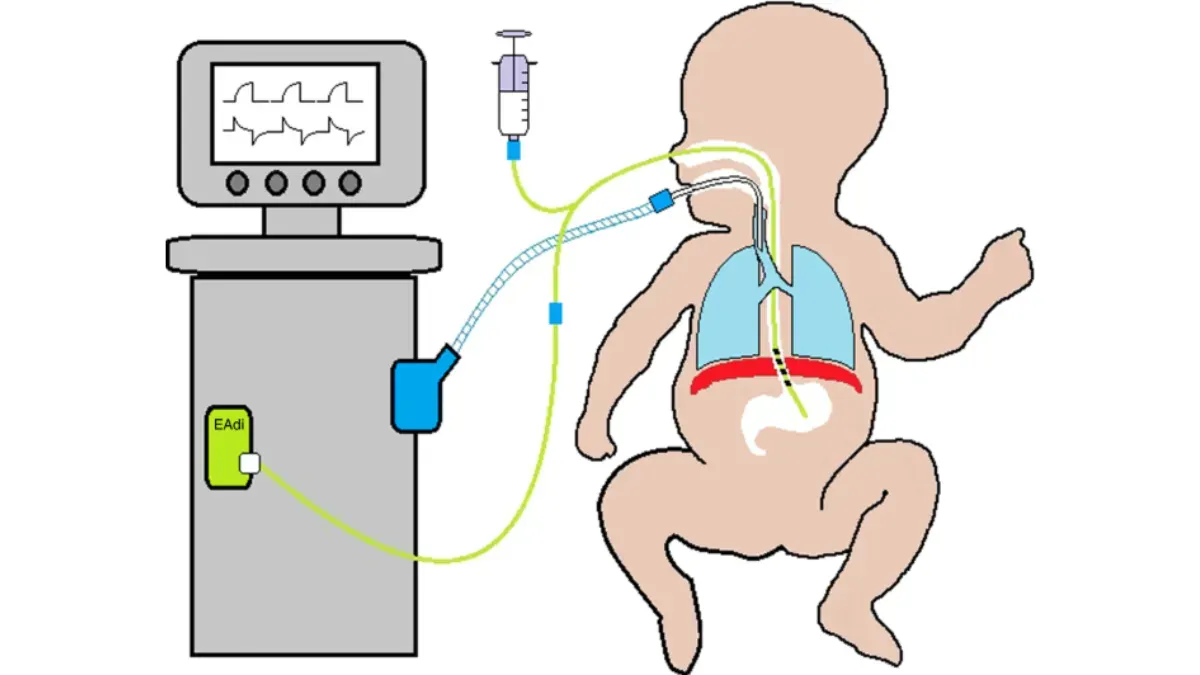

- Flexible bronchoscopy (gold standard)

- Assesses airway dynamics and requires precise anaesthesia and use of the smallest scope available, to prevent stenting the airway with the scope.

- The child must be breathing independently so that any dynamic component to the collapse can be observed.

Management

- This depends on symptom severity and whether the tracheomalacia is primary or secondary.

- Mild tracheomalacia (<75% collapse) usually resolves by age two without intervention, but parents need reassurance and CPR training if “dying spells” occur.

- Severe cases (>75% collapse) may require treatment.

- Conservative measures such as prone positioning and head elevation often help, but supplemental oxygen or continuous positive pressure devices may be needed if ineffective.

Medical

- Supportive care

- Lung hygiene (smoking cessation, immunisation).

- CPR training for caregivers.

- Gastroesophageal reflux management using proton pump inhibitors.

- Non-invasive ventilation (CPAP/BiPAP) for severe cases

- May require tracheostomy if continuous support is needed.

- Insufficient evidence, therefore not recommended:

- Beta-agonists (may worsen tracheomalacia).

- Chest physiotherapy.

- PEEP devices.

Surgical

- Indications

- Life-threatening events.

- Cyanosis.

- Severe feeding difficulties.

- Failure to extubate.

- Recurrent infections.

- Procedures

- Tracheostomy

- Previously the mainstay of treatment, now reserved for cases where non-invasive therapy fails.

- Not useful for distal tracheal involvement.

- Aortopexy – pulls the aorta anteriorly to relieve tracheal compression, often used in tracheoesophageal fistula–related tracheomalacia.

- Tracheopexy

- Anterior tracheopexy (uses tracheal traction sutures).

- Posterior tracheopexy (suturing the posterior tracheal membrane to the spine for stabilisation via posterior right thoracotomy).

- Tracheal resection – for short-segment severe cases unresponsive to other interventions.

- Tracheal stenting – rarely used in children, reserved for cases where tracheostomy is not an option.

- Intraoperative bronchoscopy helps guide surgery by assessing real-time airway improvement.

- Tracheostomy

- Secondary malacia

- Unlike intrinsic malacia, as the child grows this fixed obstruction is likely to further impinge on the airway and weaken the cartilaginous support.

- Treatment of the underlying cause (e.g., vascular ring ligation) is essential.

Prognosis

- Most cases improve by 1–2 years of age as the airway grows stronger and firmer, but some children may still have chest symptoms with exercise as they get older.

- Severe cases may persist, requiring long-term support or surgical intervention.

- Patients with secondary tracheomalacia depend on management of the underlying condition.

References

- Wallis, C., Alexopoulou, E., Antón-Pacheco, J. L., et al. (2019). ERS statement on tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children. European Respiratory Journal, 54(1900382). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00382-2019

- Kamran, A., & Jennings, R. (2019). Tracheomalacia and Tracheobronchomalacia in Pediatrics: An Overview of Evaluation, Medical Management, and Surgical Treatment. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 7, 512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00512.

- Barreto, C., Rombaldi, M., Holanda, F., Lucena, I., Isolan, P., Jennings, R., & Fraga, J. (2024). Surgical treatment for severe pediatric tracheobronchomalacia: the 20-year experience of a single center. Jornal de Pediatria, 100, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2023.10.008