Pulmonary Haemorrhage

Pulmonary Haemorrhage

Dec 03, 2025

Pulmonary Haemorrhage

Pulmonary haemorrhage is not uncommon in paediatric respiratory practice and can present with a wide spectrum of severity. Early recognition is essential, as identifying the precise source of bleeding — whether airway, lung parenchyma, or extrapulmonary — is crucial for guiding accurate diagnosis and management. Prompt, targeted intervention improves outcomes and helps prevent recurrence or complications.

Introduction

- Pulmonary haemorrhage is a condition which results in the extravasation of blood into the lung airways, parenchyma or alveoli.

- It can either be from the bronchial circulation or the pulmonary circulation and can either be focal or diffuse bleeding.

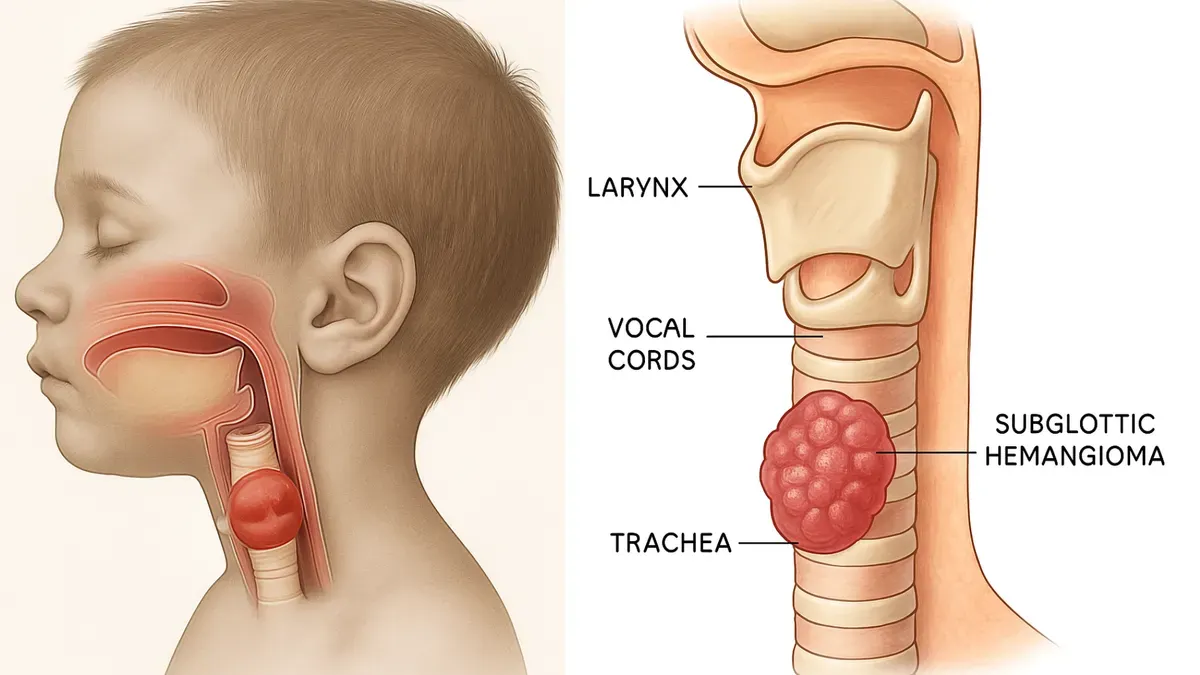

- The cause of focal pulmonary haemorrhage is usually from the airways and is frequently from the bronchial circulation and spares the alveoli.

- Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH) occurs when there is bleeding as a result of injury to the pulmonary capillaries, venules or arterioles.

- DAH leads to blood filling the alveolar spaces and can rapidly compromise gas exchange.

- This chapter focuses on diffuse alveolar haemorrhage in children.

Table 1: Causes of Haemoptysis

| Focal haemorrhage | Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage |

|---|---|

|

Immune mediated:

Non-immune mediated:

|

Table 2: Mimics of Haemoptysis

| Mimics |

|---|

|

Clinical Presentation

Diagnosis

- Classic triad of haemoptysis, chest infiltrates and anaemia.

- In children, haemoptysis may be absent and present as cough.

- Usually normocytic, normochromic anaemia; if chronic, may be microcytic hypochromic.

History

- Recurrent respiratory symptoms; may or may not report haemoptysis.

- Treated for anaemia but not responding to therapy.

- Underlying clinical conditions:

- Connective tissue disease.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Renal disease.

- Infections including pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Congenital malformations.

- Cardiovascular disease.

- Bleeding disorder.

Clinical signs

- As above, with signs of underlying condition.

- Acute respiratory distress (if acute bleed).

- Tachypnoea.

Investigations

Blood

- Full blood count (FBC), reticulocyte count.

- Coagulation screen (INR, fibrinogen).

- Immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgE).

- *Autoimmune screen:

- Rheumatoid factor.

- Anti-dsDNA (double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid).

- ANA (antinuclear antibody).

- p-ANCA (perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies).

- c-ANCA (cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies).

- Anti-ribonucleic acid antibodies.

- Factor VIII.

- Von Willebrand’s factor.

- Anti-GBM (glomerular basement membrane) antibodies.

- Anti-MPO (myeloperoxidase) antibodies.

- Anti-PR3 (proteinase 3) antibodies.

- Cow’s milk allergen IgE.

- Coeliac IgA transmutase.

- Urine dipstick.

Bronchoscopy

- Blood or blood-stained fluid; identification of cause of bleed (congenital malformations, lymph nodes, pulsatile masses, pulmonary tuberculosis lesions, etc.).

- Bronchoalveolar lavage: haemosiderin-laden macrophages, free iron.

Chest radiograph

- Findings depend on nature of bleed.

- Diffuse lung changes.

- Acute/massive bleed:

- Consolidation.

- “White out”.

- Chest infiltrates.

- Chronic disease:

- Chest infiltrates.

- Interstitial changes.

- Diffuse changes.

Chest CT scan

- Ground-glass appearance with mosaic attenuation.

- Fibrosis.

- Cysts.

Echocardiogram

- Presence of congenital heart disease, arteriovenous malformations, mitral valve disease.

- Presence of pulmonary hypertension.

Lung biopsy*

- Not mandatory but can guide management.

- Tests performed (see appendix)*.

- May show haemosiderin-laden macrophages, free iron, red blood cells, fibrosis, capillaritis with or without immunoglobulins, complement factors, micro-organisms.

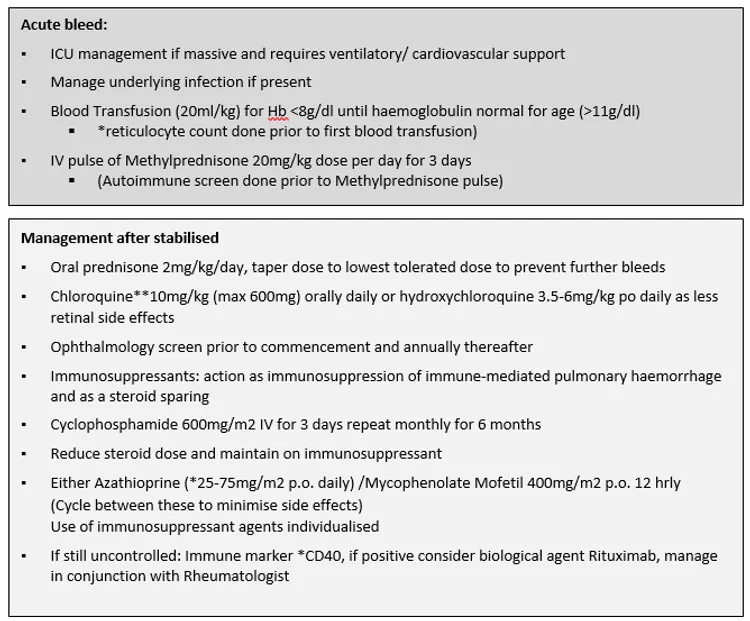

Figure 1: Management of Children with Diffuse Alveolar Haemorrhage

Follow-up

- Regular review as needed and until stable.

- FBC, reticulocyte count and chest radiograph at every visit.

- Lung function testing:

- Spirometry – in poor chronic control, restrictive pattern may be seen, although normal function is also frequent.

- DLCO (diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide), as available.

- Active bleed:

- Drop in haemoglobin and increase in reticulocyte count with or without presence of respiratory symptoms.

- Changes in lung function tests consistent with acute bleed.

- Increase in DLCO

- Chest radiograph

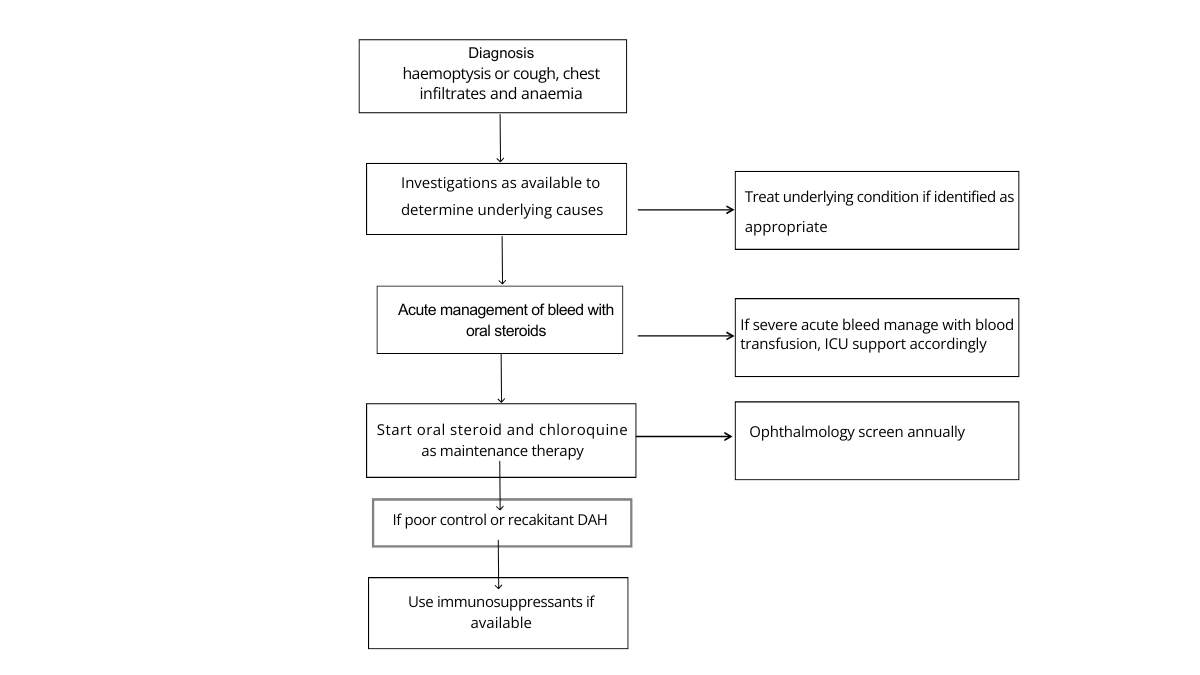

Fig 2: Algorithm for Management of DAH in a resource constrained setting.

Complications

- If repeated episodes:

- Pulmonary fibrosis.

- Respiratory failure.

- If acute massive bleed:

- Decompensation.

- Respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse.

- Death.

Prognosis

- Varies between patients.

- Depends on underlying condition.

- Aim to use lowest dose of steroids necessary for control of disease.

- Bone-protective treatment:

- Calcium supplement and vitamin D (400 IU orally daily).

- Isoniazid prophylaxis* for those on certain immunosuppressants and biologicals.

References

- Godfrey S. Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemoptysis in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004 Jun;37(6):476–84. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20020. PMID: 15114547.

- Avital A, Springer C, Godfrey S. Pulmonary haemorrhagic syndromes in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2000 Sep;1(3):266–73. doi: 10.1053/prrv.2000.0058. PMID: 12531089.

- Balfour-Lynn IM. Haemoptysis: is it really from the lungs? The well child who spits out blood. Arch Dis Child. 2023 Nov;108(11):879–883. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2022-324276. Epub 2023 Mar 29. PMID: 36990647.